For a lively walkthrough, try our audio version below; the blog complements it with complete information for reference:

Imagine the world of electronics as a surging river. If you needed more than simply “opening” or “shutting” the river, but instead precisely controlled the flow and shape of every drop, what tool would you choose?

Would you choose a responsive, precision faucet that could be adjusted at will, even amplifying a trickle into a waterfall? Or a sturdy gate, unstoppable once opened, that can only be closed by altering the upstream source?

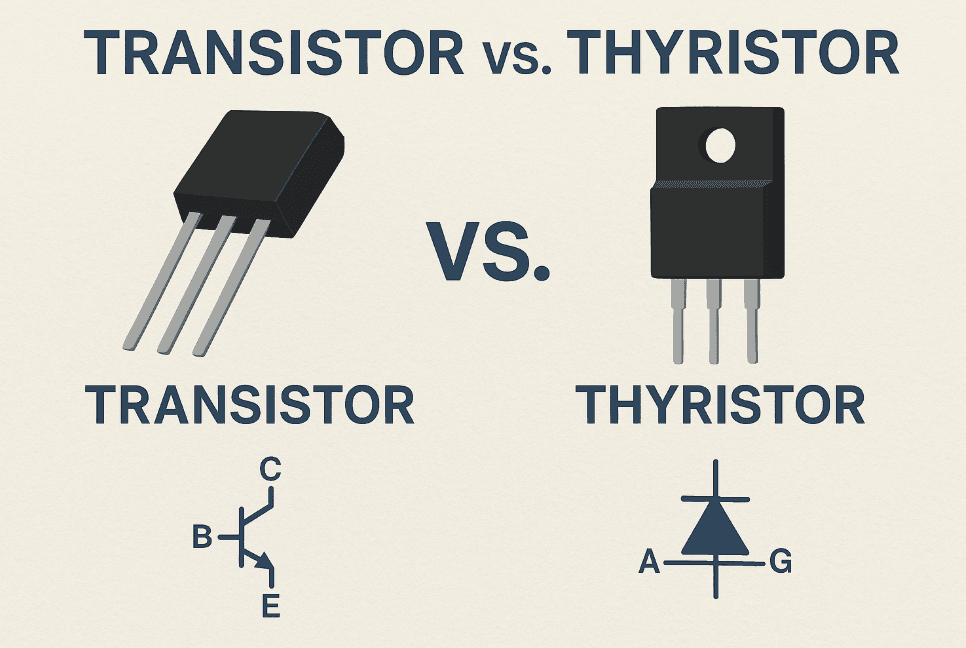

In the world of electronics, the transistor is the universal “precision faucet,” the cornerstone of our modern information society; while the thyristor is the powerful “sturdy gate,” silently supporting our industrial and energy worlds. Although both belong to the semiconductor family and are based on the magic of the PN junction, they have taken very different paths, from design philosophy to application: one focuses on the precise manipulation and amplification of signals, while the other focuses on the robust switching and control of electrical power.

This article will delve into the inner workings of these two devices, analyzing their structures, uncovering their principles, reviewing their applications, and clearly explaining their fundamental differences, helping you understand the power and division of labor hidden behind circuit boards.

1. What is a thyristor?

A thyristor is a solid-state device based on four layers of alternating semiconductors (P-N-P-N). It functions as a highly efficient “power switch,” precisely controlling high voltage and high current. Its structure consists of three core terminals, each with a distinct function:

- Anode: The input terminal where current enters the device, typically connected to the high-potential side of the circuit;

- Cathode: The output terminal where current exits the device, connected to the low-potential side of the circuit;

- Gate: The control terminal, receiving tiny external signals to control the device’s on and off states, is a crucial interface for “controlling large things with small ones.”

2. What is the working principle of a thyristor?

The thyristor’s operating process revolves around three stages: “triggering – latching – shutoff.” Its core characteristic is its ability to maintain conduction after triggering. The detailed logic is as follows:

Triggering: Simply applying a tiny electrical pulse (e.g., a few volts, a few milliamperes) to the gate terminal disrupts the equilibrium of the PN junction within the device, causing the thyristor to switch from blocking to conducting. Current now flows from the anode to the cathode.

Latching: Once successfully triggered, the thyristor enters a “latched state.” Even if the gate control signal is removed, current continues to flow as long as the main current between the anode and cathode remains at a certain level. This eliminates the need for additional control signals and significantly reduces control energy consumption.

Shutoff: To restore the thyristor to blocking mode, the main current must be reduced to below a specific threshold (the “holding current”). Common methods include reducing the circuit load, lowering the input voltage, or forcibly interrupting the current flow by applying a momentary reverse voltage through an external circuit.

3. Thyristor Applications:

Thanks to their high voltage resistance, high current, and low control energy consumption, thyristors are widely applicable to various power control needs. Applications include:

- Dimmers: By adjusting the conduction angle of the thyristor, the current output to the lamp is controlled, achieving smooth dimming of the light. These are commonly used in home lighting, stage lighting, and other applications.

- Motor Speed Controllers: In AC motor systems, thyristors are used to control the voltage or current phase of the input motor, adjusting the motor speed to meet the speed control requirements of equipment such as fans, pumps, and conveyors.

- High-Voltage Direct Current (HVDC) Transmission: In long-distance high-voltage transmission systems, thyristors serve as core components for rectification and inversion, converting AC power to DC for transmission (reducing line losses) and then converting DC back to AC for user use. They are key components in cross-regional power transmission.

- Protection Circuits: For example, “Crowbar protection circuit”: When a system experiences a surge fault such as a sudden voltage or current surge, the thyristor quickly conducts, diverting excess current into the ground loop and preventing downstream equipment (such as inverters and photovoltaic inverters) from being damaged by high voltage.

4. What is a transistor?

A transistor is a core electronic device constructed from three layers of alternating semiconductors (N-P-N or P-N-P). It implements signal control and energy conversion through three functional terminals, each with distinct functions:

Emitter (E): Responsible for injecting carriers (electrons or holes) into the device and serves as the “input” for current flow;

Base (B): Serving as a control terminal, it regulates the current flow between the emitter and collector by receiving tiny current/voltage signals, making it the key to “controlling large currents with small currents”;

Collector (C): Collects carriers injected from the emitter and regulated by the base to form the output current and serves as the “output” for current flow.

In its structure, the base layer is typically thin and has a low doping concentration. This design lays the foundation for subsequent switching and amplification functions.

5. How does a transistor work?

The core value of a transistor lies in “controlling a large signal with a small signal.” Depending on the application scenario, it can be divided into “switching mode” and “amplifying mode.” The specific logic is as follows:

- As an electronic switch:

When a control current (or voltage) that meets the threshold is applied to the base, the equilibrium of the emitter-base and base-collector PN junctions is disrupted, allowing carriers to flow smoothly from the emitter to the collector. In this state, the transistor is in the “on” state, equivalent to a “closed switch” in the circuit, allowing large current to flow.

When the base control signal is removed, the PN junction returns to its reverse biased state, blocking the carrier path and the transistor enters the “off” state, equivalent to an “open switch,” shutting off the main current path. This switching speed is extremely fast (nanoseconds) and requires no mechanical action, making it suitable for high-frequency switching scenarios.

- As a signal amplifier:

Based on the characteristic of “base current controlling collector current,” when a weak electrical signal (such as audio or radio frequency) is input to the base, the collector outputs a signal with the same waveform as the input signal, but with an amplitude amplified by tens to thousands of times.

The core logic is that a small change in the base current causes a proportional change in the collector current (the amplification factor is determined by the transistor’s own parameters), thereby achieving “small input signal driving large output signal,” effectively enhancing signal strength and meeting the signal requirements of subsequent circuits.

6. Transistor Applications:

Due to their advantages of small size, low power consumption, fast switching speed, and stable amplification performance, transistors have become an essential component of electronic devices. Applications include:

Computer field: In microprocessors (CPUs) and memory chips (RAM), billions of tiny transistors represent the binary “1” and “2” in their “on/off” states. “0” forms the fundamental unit of logical operations and data storage, supporting high-speed computer processing.

Audio equipment: In audio amplifiers in speakers and headphones, transistors amplify weak audio signals from sound sources (such as microphones and player output), providing sufficient power to drive the speakers and reproduce clear sound.

Mobile communications equipment: In mobile phones and base stations, transistors amplify weak radio frequency signals (ensuring signal clarity) and adjust power output to meet the signal requirements of different communication distances, while also reducing device energy consumption.

Automotive electronic systems: In modern car engine control units (ECUs), transistors act as switching elements, precisely controlling the on-off timing of fuel injectors and ignition coils to optimize engine combustion efficiency. Furthermore, transistors play a crucial role in signal conversion and power control in systems such as vehicle air conditioning, lighting control, and airbag activation.

7. The Difference Between Thyristors and Transistors

Quick Preview:

| Feature | Transistor | Thyristor |

|---|---|---|

| Function | Fine signal control, amplification, switching | High-power directional control |

| Structure | 3-layer (N-P-N or P-N-P) | 4-layer (N-P-N-P) |

| Control | Base/gate small signal modulates current | Gate pulse triggers conduction; shutoff requires current < holding current |

| Modes | Cutoff, Amplification, Saturation | Two-state: blocking or conducting |

| Current/Voltage | Low-voltage, low-current precision | High-voltage, high-current capacity |

In the semiconductor technology ecosystem, thyristors and transistors are both important devices, but due to different design objectives, they exhibit significant differences in function, structure, and operating mode. They are suited for two major applications: signal control and power control, respectively. A specific comparison is as follows:

Functional Positioning: Fine Signal Control vs. Directed Power Management

Transistors: Their core function is fine control of electronic signals, combining signal amplification and switching capabilities. They can amplify weak input signals (such as audio and radio frequency signals) or perform high-frequency, precise switching operations, converting electrical inputs into “fine-tuned outputs” suitable for subsequent circuits. They are components for signal processing and logic control in electronic circuits.

Thyristors: Their core function is the directional management of high-power currents. Based on unidirectional conduction, they specialize in switching and power regulation in power supply applications. By stably controlling the switching of high voltages and high currents, they improve the efficiency and reliability of power systems. They are devices that promote the implementation of power electronics technology in industrial applications.

Structural Design: Three-Layer Flexible Adaptation vs. Four-Layer Directed Activation

Transistors utilize a three-layer semiconductor structure and can be categorized by type as either bipolar junction transistors (BJTs, such as NPN/PNP) or field-effect transistors (MOSFETs, consisting of source, gate, and drain). This structure modulates the flow of carriers between the emitter (or source) and collector (or drain) by controlling the current/voltage at the base (or gate). Its simple and flexible structure adapts to diverse signal control needs.

Thyristors utilize a four-layer alternating semiconductor structure (N-P-N-P) with three terminals: anode, cathode, and gate. This unique four-layer structure requires a specific trigger signal (electric pulse) applied through the gate to activate conduction. Once conducting, it requires specific conditions (such as the current falling below the holding current) to shut down. Its structural design emphasizes high-power blocking and directional conduction, requiring precise synchronization of control logic within the circuit.

Operating Modes: Multi-state Fine Adjustment vs. Dual-state Efficient Switching

Transistors operate in three modes: cutoff, amplification, and saturation.

- In cutoff, current flow is blocked.

- In amplification, a small base signal controls a large collector current.

- In saturation, the transistor acts like a closed switch with low resistance.

This multi-state behavior allows transistors to handle both signal amplification (e.g., audio circuits) and logic operations (e.g., CPU switches), balancing signal accuracy and fast response.

Current and Voltage Capacity: Low-Voltage Precision Control vs. High-Voltage Strong Load

Transistors: Typically suited for low-current, low-voltage applications (e.g., a few amperes, tens of volts). Their design focuses on “fine control” and “low power consumption,” requiring a balance between efficiency and signal accuracy within a low-power range. They are not suitable for high-voltage, high-current environments.

Thyristors: With their high-voltage, high-current carrying capacity (e.g., thousands of volts, thousands of amperes), they can handle harsh power environments reliably and efficiently manage industrial-grade energy distribution and transmission. They are crucial components in high-voltage power systems and high-power equipment, requiring integrated circuits for implementation. “High-Power Safety Control.”

Whether the application requires fast switching and signal amplification, or the power control system pursues high voltage and high current carrying capacity, selecting components with matching performance is crucial to a successful design. Excellent ideas require reliable components to steadily move from the drawing board to reality.

We believe that a deep understanding of the characteristics of components like transistors and thyristors is just as important as ensuring a stable supply. As you embark on your next innovative project, having a trusted partner with both technology and resources can make your journey smoother. 7SEtronic is always here. Follow us on LinkedIn for updates. Explore more insights in our Tech Blog, where we share practical guides, component comparisons, and the latest updates in semiconductor technology to help engineers make smarter design decisions.