In the long history of power electronics technology, the birth of the thyristor marked a major breakthrough in humanity’s ability to control electrical energy. From theoretical exploration at Bell Labs to commercialization by General Electric, this four-layer semiconductor device, with its unique “trigger-lock” characteristic, achieved a technological breakthrough in controlling vast amounts of energy with tiny signals.

Today, whether we adjust light brightness, control motor speed, or use electric vehicle charging stations, thyristors are silently acting as “power switches” behind the scenes. They not only laid the foundation for modern power control technology but also maintain their unrivaled position in the high-voltage, high-current field, despite competition from newer power devices like IGBTs and SiC. This article will analyze the structural secrets and operating logic of this classic device, explaining how it achieves precise power control with its simple semiconductor structure.

1. The Development of Thyristors

The development of thyristors has been a gradual process, from theoretical exploration to prototype development and commercialization. Its predecessor was the silicon-controlled rectifier (SCR), developed by General Electric (GE) in 1957. The technological roots can be traced back to the early research of William Shockley and Bell Telephone Laboratories. In 1950, Shockley first proposed the theory of a four-layer (p-n-p-n) semiconductor device composed of alternating p-type and n-type materials. His Bell Labs colleagues J. J. Ebers and John Moll later further explored this concept, developing the “two-transistor model” to explain the switching principle of this structure and laying the theoretical foundation for device development.

In 1956, Moll and Morris Tanenbaum’s team at Bell Labs achieved key progress, developing and publishing detailed technical information for the four-layer switching device, forming the initial prototype of the thyristor. GE’s power engineering team then took over the task of optimizing the device. In 1957, Gordon Hall led the team in developing a three-terminal p-n-p-n device, with Frank “Bill” Gutzwiller spearheading its commercial adaptation. In 1958, GE officially marketed the device under the trademark “silicon-controlled rectifier (SCR),” marking the beginning of its commercial production and application. By the 1960s, the term “thyristor,” a combination of “thyratron” and “transistor,” had gained international recognition and achieved standardization. The device was originally designed to replace traditional gas-filled vacuum tubes.

2. What is a thyristor?

A thyristor is a highly efficient, high-power control semiconductor device that operates similarly to a one-way latching switch in electronic systems. Using a tiny trigger signal, it can precisely control load currents far exceeding its input power. This “small-to-large” capability gives it a unique advantage in power control.

Structurally, thyristors utilize a unique four-layer semiconductor structure (P1-N1-P2-N2), forming a series connection of three PN junctions. This unique construction allows for two stable operating states: a high-impedance off-state when untriggered. Once the control electrode receives an appropriate trigger pulse, the device rapidly transitions to a low-impedance on-state. This state remains conductive even after the trigger signal is removed, until the circuit current falls below the holding current or a reverse voltage is applied.

This “triggered on, current-locked” operating mechanism makes thyristors particularly suitable for applications requiring stable, high-power output. Whether in industrial motor speed control systems and AC power conditioning devices, or in dimming circuits and solid-state relays in everyday household appliances, thyristors provide reliable, high-efficiency control solutions. Their robust semiconductor structure also ensures long life and fast response, continuing to play a significant role in modern power electronics.

3. How does the thyristor structure achieve “small signal control of high current”?

The structural design of a thyristor is centered around the goal of “precisely controlling large currents with small signals.” It consists of four alternating semiconductor layers and three functional electrodes, each of which plays a specific role in current conduction and control. These components are described below:

- Semiconductor Layers: The Basic Carriers of Current Conduction and Control

The core of a thyristor is a four-layer alternating semiconductor structure: “N1-P1-P2-N2.” The N-type and P-type layers achieve functional division of labor through carrier differences:

The N-type regions (N1 and N2) serve as the outer semiconductor layers of the device. Both N1 and N2 are made of N-type semiconductor material. Their core characteristic is the presence of an excess of free electrons (negatively charged carriers) within the N-type region, providing a “carrier source” for current conduction. When the thyristor is in the on state, the N1 region (connected to the anode) and the N2 region (connected to the cathode) form the “main path” for current conduction. Free electrons migrate along this path in a directed manner, ensuring high voltage and high current flow through the device with low loss. These free electrons are the core carriers of current flow.

The P region (P1 and P2) is located between N1 and N2. Through a semiconductor doping process, the concentration of “holes” (positive charge carriers) is increased to a significantly higher concentration than the concentration of electrons, creating a complementary carrier environment to the N region. The P region is the “core current control component” of the thyristor. P1 and N1, and P2 and N2, respectively, form a PN junction. These two PN junctions act as “current valves”: when not receiving a control signal, the PN junction is in a reverse blocking state, blocking current flow. Upon receiving a gate signal, the PN junction equilibrium is disrupted, the carrier recombination state changes, and the valve opens, allowing current to flow.

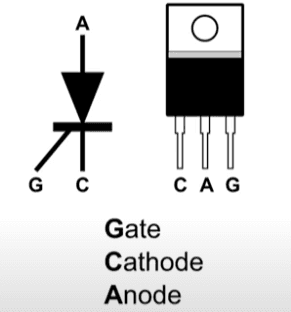

- Functional Electrodes: The Key Interface Between State Control and Current Direction

The three electrodes (gate, anode, and cathode) perform the functions of “control triggering” and “current inflow and outflow,” respectively, and serve as the interface between the thyristor and the external circuit:

The control electrode (gate) is typically connected from the P2 region (some structures connect from the P1 region) and is the “external control terminal” of the thyristor. While small in size, it plays a key role. Its core function is to receive a tiny external control signal (a few volts or a few milliamperes). This signal alters the carrier distribution in the P region, triggering a switch in the PN junction state. When the signal reaches the threshold, the thyristor rapidly switches from the “off” (current blocking) state to the “on” (current allowing) state. Once triggered, it maintains conduction without a continuous signal, significantly reducing control energy consumption.

The anode and cathode are located at opposite ends of the device, forming a clear current path: the anode is fixedly connected to the N1 region, serving as the “entrance” for current entering the thyristor; the cathode is fixedly connected to the N2 region, serving as the “exit” for current flowing out of the device. In the on state, the anode and cathode not only conduct current in and out but also restrict current flow to a unidirectional pattern: current can only flow from the anode to the cathode via N1, P1, P2, and N2, and cannot flow in the opposite direction. This characteristic makes it suitable for scenarios such as rectification and unidirectional power control, ensuring circuit stability.

- Structural Synergy: The Core Logic for Efficient Current Control

In general, thyristors utilize a “four-layer semiconductor + three-electrode” structure to create a highly efficient current control system: the N- and P-regions provide the carrier foundation, the gate switches state via a tiny signal, and the anode and cathode define the current path. This design enables the thyristor to function like an “intelligent switch”—it can be triggered to conduct with only a weak signal, and once on, it can stably conduct high currents. Ultimately, this simple structure achieves its core value of “low control energy consumption and high power handling,” making it a common component in high-power power electronics.

4. How does the thyristor’s operating logic work in each stage?

The core function of a thyristor is to precisely switch between the “off” and “on” states, triggered by an external control signal. This state change requires only a pulse signal, eliminating the need for continuous control. This characteristic makes it highly adaptable to high-voltage, high-current power control scenarios. Its operating logic can be broken down by state as follows:

- Initial State: Off (Reverse Blocking Mode)

When no control signal is received, the thyristor is in the off state by default—even when a positive voltage is applied between the anode and cathode, current cannot flow. This characteristic stems from the two PN junctions (P1-N1 and P2-N2) formed by its internal “N1-P1-P2-N2” four-layer structure. At this point, both PN junctions are reverse-biased, making it difficult for charge carriers to cross the potential barrier formed by the junctions. This acts as an “invisible barrier” in the circuit, structurally blocking the flow of current and ensuring stable current flow in the absence of a control signal.

- Trigger Phase: Turn-On (Forward Conducting Mode)

To turn the thyristor from off to on, a small trigger current (or voltage) is applied to the gate (control terminal). This trigger signal alters the carrier distribution in the P2 region, disrupting the reverse-bias balance of the PN junction. Specifically, the gate signal injects holes into the P2 region, causing the P2-N2 junction to shift from reverse bias to forward bias, thereby lowering the potential barrier across the entire device. When the potential barrier drops to a critical value, current can flow from the anode to the cathode via N1-P1-P2-N2, officially transitioning the device into the on state. Crucially, once turned on, the thyristor remains on even after the gate trigger signal is removed, as long as the anode-cathode current remains above the “holding current” (a device-specific parameter). This eliminates the need for additional control signals and significantly reduces control energy consumption.

- Stabilization Phase: Latched On

After turning on, a thyristor enters a “latch state,” functioning like a closed switch, allowing full current to flow steadily through the circuit. The key to this phase is the continuous recombination and flow of carriers: after turning on, a large number of electrons move from the N region to the P region, and holes move from the P region to the N region. This continuous recombination of carriers forms a stable current path. Even without a gate signal, this path is sustained by current flow until external conditions change.

- Reset Phase: Turn-off Operation

To switch a thyristor from on to off, the key is to reduce the current between the anode and cathode to below the “holding current.” There are two common ways to achieve this:

Passive Method: By reducing the load (e.g., reducing the total circuit power), the current flowing through the device naturally drops below the holding current, disrupting the carrier path and restoring the device to off.

Active Method: By momentarily applying a reverse voltage between the anode and cathode, the current flow is forcibly interrupted, quickly shutting off the current path. In addition, special types of thyristors (such as gate turn-off thyristors (GTOs)) do not rely on current or voltage changes. Simply applying a negative signal to the gate directly disrupts carrier equilibrium, achieving active turn-off, making them suitable for more complex and rapid control scenarios.

5. Thyristor Types

The thyristor family is divided into types suitable for different scenarios based on their conduction direction and control method. Each device has its own emphasis on characteristics and functions. The classification and application descriptions are as follows:

- Silicon-controlled rectifier (SCR)

Core Characteristics: As the most basic type of thyristor, SCRs are unidirectional devices that conduct current in only one direction when triggered by a trigger signal. Once turned on, they require external means (such as reducing the current to below the holding current) to shut down.

Applicable Applications: Due to their high reliability in high-power control, SCRs are widely used in applications requiring precise control of high-power loads, such as industrial motor speed control and power-frequency rectifier equipment (converting AC to DC).

- Bidirectional Thyristor (TRIAC)

Core Features: It transcends the limitation of unidirectional conduction and can conduct current in both the positive and negative half-cycles of an AC circuit. It is also triggered by a gate signal, enabling full-range power control within the AC cycle.

Applications: Because they meet the bidirectional power control requirements of AC circuits, TRIACs are commonly used in residential and light industrial applications requiring flexible power regulation, such as home light dimmers, fan speed controllers, and small AC motor speed controllers.

- Bidirectional Trigger Diode (DIAC)

Core Features: It is essentially a bidirectional voltage-triggered device. It remains blocked until a specific breakdown voltage is reached and automatically turns on when the voltage in either direction reaches a threshold. After turning on, it will only resume blocking when the current drops below a critical threshold.

Applications: It does not directly control power itself but is primarily used in conjunction with a TRIAC to provide sharp, stable trigger pulses, optimizing control accuracy in AC switching scenarios. It is commonly found in AC control circuits for appliances such as washing machines and air conditioners.

- Gate Turn-Off Thyristor (GTO)

Core Features: It possesses bidirectional gate control capabilities. A positive gate signal triggers conduction, while a negative gate signal directly shuts off the diode, eliminating the need for external circuitry to reduce current. This provides greater flexibility and faster switching speeds than SCR control.

Applications: Suitable for complex, high-power applications requiring rapid and frequent state switching, such as inverters (converting DC to AC), large AC motor drives, and power conversion units in renewable energy power generation systems.

6. Diodes, Transistors, and Thyristors: Comparison of Functional Logic and Application Scenarios

Among semiconductor devices, each has distinct functional logic and application scenarios. The differences are as follows:

Control Method and State Maintenance

Diodes: They have no control function and conduct electricity in only one direction. Their on/off state is determined solely by the direction of current flow.

Transistors: They require a continuous gate signal to maintain their on/off state; removal of the signal triggers a change in state.

Thyristors: They require only a pulse signal to switch “on/off.” After switching, they require no continuous control, relying on the current itself to maintain their state. High-Power Adaptability

Diodes: They lack current control capabilities and are only suitable for simple applications such as rectification and freewheeling, but are unable to handle high voltages and high currents.

Transistors: They are more suitable for small and medium-power control, but have high power consumption during continuous control, high losses under high voltages and high currents, and low reliability.

Thyristors: They have low energy consumption and can withstand high voltages and high currents, making them a common and important component in applications such as industrial rectification and high-power motor control.

7. Advantages and Applications of Thyristors

Thyristors offer unique advantages in high-power control, enabling them to precisely control currents of hundreds of amperes with extremely small drive signals. These semi-controlled devices maintain conduction once the gate is triggered, demonstrating excellent reliability in applications such as AC voltage regulation and motor control. Their four-layer semiconductor structure enables them to withstand high voltage surges, and combined with their low forward voltage (typically 1-2V), they significantly reduce system energy consumption.

In practical applications, thyristors can be used as phase-controlled dimming elements and as core components in motor soft starters. In industrial welding equipment, they ensure precise timing control of current flow; in electric vehicle charging stations, they enable stable AC-DC conversion. This device is also widely used in power switching circuits in emergency lighting systems and pulse generation modules in communications equipment, demonstrating its comprehensive adaptability from consumer electronics to industrial power systems.

8. Competition and Competitiveness between Thyristors and Modern Power Devices

With the increasing popularity of new power devices such as IGBTs and SiC MOSFETs, the application of thyristors has shrunk, but they remain irreplaceable in specific areas, complementing the “competitive and complementary” relationship between the two:

Traditional thyristors (such as SCRs)

Advantages:

- Strong high-voltage and high-current capabilities (supporting up to 10kV+ and several thousand amps);

- Low cost and high reliability (simple structure and shock resistance);

- Suitable for low-frequency, high-power applications (such as industrial frequency rectification).

Disadvantages:

- Slow switching speed (not suitable for high-frequency applications, such as induction heating above 20kHz);

- Complex shutdown (requires reverse voltage or current reduction).

Important applications: High-voltage direct current (HVDC), industrial frequency rectifiers, large welding equipment, and mining locomotives.

Advantages:

- Fast switching speed (nanoseconds, compared to microseconds for thyristors);

- Flexible control (capable of high-frequency switching, suitable for variable-frequency applications);

- Low loss (suitable for high-frequency power supplies and new energy vehicles)

Disadvantages:

- High cost for high voltage and high current (prices above 10kV are significantly higher than those of thyristors);

- Weak surge resistance (prone to sudden high voltage breakdown).

Important Applications: New energy vehicle inverters, photovoltaic inverters, high-frequency switching power supplies, and household variable-frequency appliances.

Conclusion: The two are not “substitutes,” but rather “complementary” in their use cases—thyristors are used in high-voltage, low-frequency, and low-cost applications, while IGBTs/SiC devices are used in high-frequency, flexible control applications.

From theoretical exploration to commercialization, thyristors, with their simple “four-layer semiconductor + three-electrode” structure and unique “trigger-lock” mechanism, have established a firm foothold in the power electronics field for nearly seven decades. They have not only achieved technological breakthroughs in “small-signal control of large currents,” but also, through iterations of sub-types like SCRs, TRIACs, and GTOs, have expanded to cover diverse applications, from industrial motor control and high-voltage rectification to home dimming and electric vehicle charging. They serve as a bridge between basic power control and complex industrial applications.

Even with the rise of new devices like IGBTs and SiC MOSFETs, thyristors remain irreplaceable in low-frequency, high-power applications such as HVDC transmission and large-scale welding equipment, thanks to their strong high-voltage, high-current capability, manageable cost, and high reliability. They complement these new devices, forming a complementary landscape: “High-frequency, flexible control relies on new devices, while high-voltage, low-frequency stability relies on thyristors.” This “symbiosis of classic and innovative” characteristics also makes thyristors a consistently important design option for power electronics engineers.

For projects requiring stable power control in high-voltage, low-frequency scenarios, or balancing cost and reliability, accurately matching thyristor types and understanding their compatibility with other components are crucial for ensuring efficient system operation. Whether selecting industrial-grade SCRs or optimizing civilian TRIAC applications, professional technical support and reliable component supply ensure smooth project progress. This is the value of 7SE‘s continued dedication to the power device field, providing customized solutions for diverse scenarios.